Wer auf LinkedIn in den Themenkosmos rund um Kunststoffverpackungen einsteigt, kommt an ihm nur schwer vorbei: Chris DeArmitt. Der Kunststoffexperte ist Berater, Keynote Speaker, Trainer, Erfinder, Autor – und vor allem ein echter Problemlöser. Als Gründer von Phantom Plastics bietet er Beratungsleistungen für den gesamten Produktentwicklungsprozess von Polymeren und Kunststoffen sowie maßgeschneiderte Lösungen für vielfältige Herausforderungen dieser Industrie an. Der studierte Chemiker hat nicht nur einen Doktortitel in „Polymere & Surface Science“ der University of Sussex, Großbritannien, sondern auch eine Leidenschaft für die Wahrheit. Und diese fehlt ihm in der öffentlichen Debatte rund um Kunststoffverpackungen. Ein Umstand, den er nicht hinnehmen will: Um Mythen rund um Kunststoff zu entkräften, hat er rund 4.000 wissenschaftliche Studien gelesen und teilt sein Wissen, wann und wo immer er kann. Rund 400 der Studien bilden die Grundlage für sein Buch „The Plastics Paradox“.

Wir haben mit dem gebürtigen Briten, der in Ohio in den USA lebt, in seiner Muttersprache gesprochen. Das Gespräch drehte sich um seine Leidenschaft für Wahrheit, sein Engagement für einen fairen Umgang mit Kunststoffverpackungen und darüber, dass wissenschaftliche Fakten häufig unbeachtet bleiben.

Chris, what motivated you to focus intensively on the topic of plastics, its effect on the environment and the circular economy?

That’s a good question, because the environment is not one of my passions. But one of my passions is truth, because I am a real scientist. When my daughters came home from school and they’ve been told utter nonsense by their teachers about plastics, I was upset. Especially as I pay taxes to live in a nice school area to send my daughters to a good school. To find out that they’ve been taught nonsense was really disheartening. Because children who are taught nonsense can’t filter it out. They grow up to vote for these things which are based on fiction, which is not good for anyone.

What have you done about it?

I realized: How are the teachers supposed to know the truth? They’re not scientists, they don’t have time to check anything. And because I’m a problem solver by profession, I read about 4.000 scientific studies on ocean plastics, marine degradation, microplastics toxicity, effects on wildlife, litter and waste by myself to find out the truth. If you don’t cover all topics, you don’t really understand the problem and you can’t come up with solutions that work. An important thing to mention is that I did all my research for free. People assume when you have a book, that you’re trying to sell the book. But it’s free in five languages on my website. Even people in our industry think that I’m secretly being paid by somebody when I’m just someone who thinks there’s no way to solve a problem if you don’t start with things that are true.

Your book “The Plastics Paradoxon” deals with myths and facts about plastics. Which three myths about plastic are the most widespread – and why?

One of them is that we’re drowning in plastics. If you look at all the materials we use, plastics are less than one percent by weight or by volume. Anyone who thinks we’re using too much material is correct. We are wasteful. We’re buying things we don’t need. So, we should cut back on using materials. But anyone who thinks we can solve the problem by talking about plastics and ignoring the other 99 percent of materials is insane. The idea here is not plastics are harmless, let’s just keep doing it. The idea here is throwing anything away after a single use is wasteful.

Another one is that people think plastics are increasing harm. But if you look at life cycle studies, which are the only way to know scientifically what causes more and what causes less harm, plastics are almost always the greenest solution. There was a recent study that proves 93 percent of the time replacing plastic packaging increases harm. They looked at 16 different applications and in 15 of them, plastic clearly reduced impact compared to metal, wood, glass or any of these other materials that we could use. Plastic creates impact and I’m not hiding that. But encouraging people to spend more money to move to other materials that increase greenhouse gas, waste and litter is in fact a terrible plan.

© Chris DeArmitt

A third one is that plastics are growing and therefore they’re bad. It’s correct, we’re using more and more every year. But the growth rate for plastics is three or four percent. That’s the same as all the other materials. And plastics is less than one percent of the total.

When plastic is not worse or even better than other materials, why are people so focused on it?

One thing is that telling lies for money is very profitable. NGO’s like Greenpeace are one example. They started with the right intention, but often, some greedy people took over and just started telling lies for money. Even the former president of Greenpeace resigned in frustration and claims that the organization relies on spreading falsehoods to secure donations. He even wrote a book about it.

With social media, people are able to make things up. And it’s not just the media: Politicians are paying organizations that tell nonsense about plastics to get the votes, whether or not that improves the environment. People never suspect NGOs, they still trust them as if they care about the environment. They don’t trust me because I’m a “plastics guy” – and they don’t have to. The studies I read can be found in Google in seconds. You can just go, click and read it yourself.

Which myths are actually based on existing problems with plastics that urgently needs to be solved?

So far, I haven’t found any accusations against plastics specifically that are true. We use too much material, we generate too much waste and there is litter. Those are real problems, but none of them are due to plastic. If you look at the alternatives, they increase waste, harm and litter. And that’s the thing that people never ask. A study compared PET bottles, for example, with laminated paper cartons. There are four materials in there to make them waterproof. But anyway, they look like a paper carton. They found out that people didn’t drop their PET bottles, they instead put the cap back on, kept the water and kept drinking it. Whereas the paper carton, they just dropped it on the floor at a much higher rate of litter than the PET bottle.

© Chris DeArmitt

To what extent do media reports contribute to misunderstandings or myths about plastic and thus to public perception?

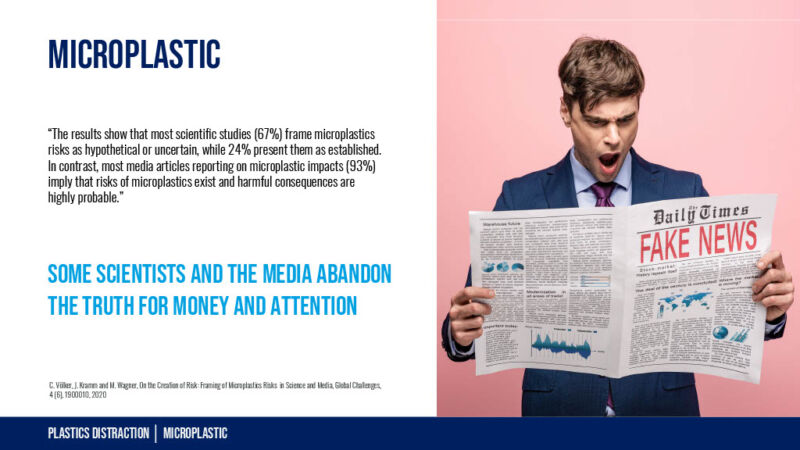

If you compare the media coverage to the facts, they’re completely misaligned. The media have long abandoned facts. It’s been scientifically proven that the media are lying to us about plastic: A study proves that 93 percent of media articles tell that microplastics are a definite threat to our health. And this is why people are worried about them. By the way: People are worried about articles from the media, that that people say they don’t trust. Then, the study looked at all the scientific articles on microplastics – and found that only a very small minority said that there was a problem. Another thing I don’t like is that we see people talking about “plastic pollution”. Pollution sounds like it comes from a company, and we need to blame a company or a material. This pollution has been proven scientifically to be litter and the solutions to litter are education, deposits and fines.

© Chris DeArmitt

Why is the reporting on plastic so biased and negative despite representative studies that prove the opposite?

The Media are following the money the same as these green groups are. They only care about getting sensational headlines and publishing anything that gets a click and an advertising dollar. I wrote to many journalists of the environment and all the top places, like New York Times, Washington Post, Reuters, Bloomberg, BBC and so on to talk about the facts and some science to support every single statement made – without success. I’m not even saying that they wouldn’t agree with me. But lies are much more exciting than the truth. The fact that we’re not in trouble is not a headline, it’s not news.

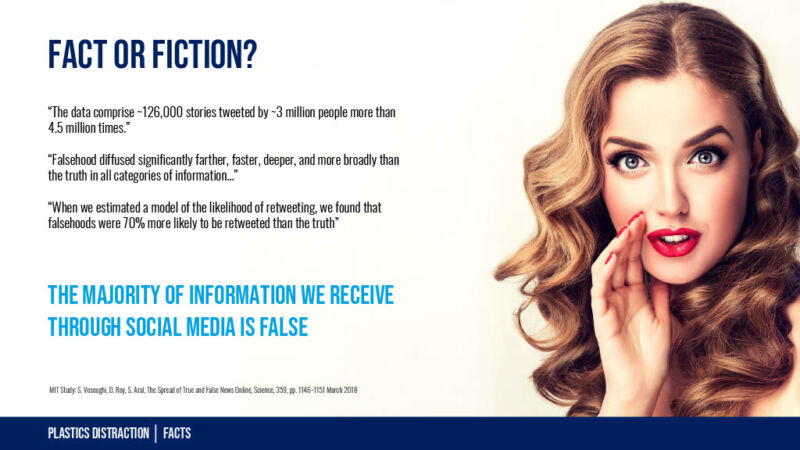

What role do social media play compared to or in addition to traditional media in spreading facts and fakes about plastic?

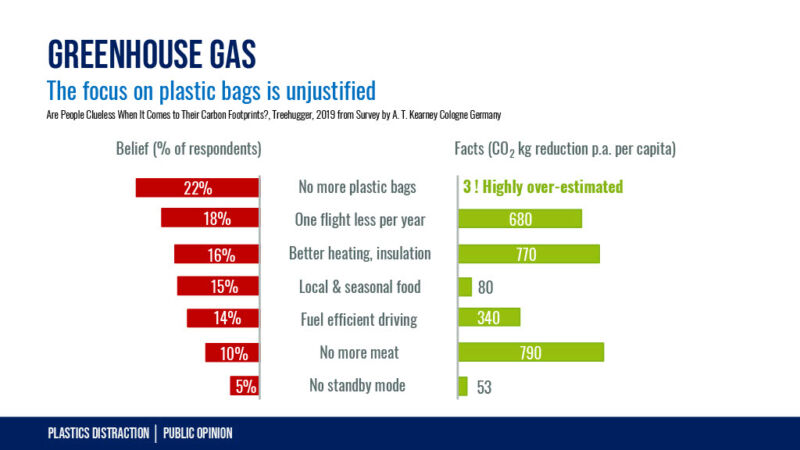

Social media makes it very cheap to spread nonsense and nobody checks it. And that’s a problem. The other thing is: It’s all about virtue signaling. Social media is a place where people try to look glamorous. It’s about people pretending to look good or be good, but being good is a lot more work. It involves spending a few minutes to check the facts and take the right action. They did a study in Germany and Italy, where they asked people “What do you think would make a difference?”. The participants think that the number one thing they could do is to get rid of plastic bags. But it turns out getting rid of plastic bags is a terrible idea, it makes things worse. The three main things you can do that would help the environment are driving less, flying less, and eating less meat. But nobody wants to do those things – they want to buy a cotton bag and swing it around their head like some virtue signaling angel, when in fact they’re spending more money to increase harm.

© Chris DeArmitt

What can the industry do to correct these myths and to get the facts out?

I think the analogy is there, the story is there, the data is there, but the industry is too quiet. We have the facts, but we need to make sure that normal people hear and see them. We must confront them with the truth in their everyday lives in a creative way to get their attention. The industry has allowed lies about plastics to spread for years. Now, I think we must spend a lot of money. Not to defend the industry, but to defend the environment and to get the truth out there to talk.

But what’s the catch?

Not all of them of course, but many of the green groups, the big ones, have sold out. They should never be allowed to advise governments, be in front of Congress, to advertise things on TV or social media which are lies. They should be sued and bankrupted. It takes away all of their money and advertising dollars, what shows the public that they’re not honest. That’s probably the best thing we could do to correct this. Unfortunately, companies don’t want to be involved in that kind of stuff. They don’t want to be involved in lawsuits. They don’t ever want to be seen in a conflict. So they’re just being killed because they’re too afraid to really take action. Beyond that, smart companies should just be brave enough to stop doing things like switching to alternatives, which increase harm. I’d like to see more of that. And I’d like to see more people standing up, asking “I’d like to see what impact materials and actions really have”.

Thank you very much, Chris!

Über Chris DeArmitt:

Chris DeArmitt gilt als einer der bekanntesten Experten für Kunststoffmaterialien, weshalb Unternehmen wie HP, Apple, P&G, iRobot, Eaton, Total und Disney ihn um Unterstützung bitten. An der University of Sussex schloss er zunächst sein Bachelorstudium der Chemie mit Schwerpunkt Polymerwissenschaften ab, gefolgt von einem Masterstudium und seiner Promotion im Bereich der Polymer- und Oberflächenwissenschaften. Im Jahr 2020 veröffentlichte er sein Buch „The Plastics Paradox“, den ersten umfassenden wissenschaftlichen Überblick über Kunststoffe und die Umwelt, der Themen wie Abfall, Littering, Mikroplastik, Zersetzung, Kunststoffe in den Meeren und mehr abdeckt. Er hält eine Vielzahl von Patenten und hat zahlreiche Artikel, Buchkapitel, Enzyklopädieeinträge und Konferenzvorträge verfasst. Als bereits mit Preisen ausgezeichneter Keynote Speaker teilt er sein Wissen über die Wissenschaft der Kunststoffmaterialien und die Auswirkungen von Kunststoffen auf die Umwelt mit einem weltweiten Publikum.